Achieving health goals for chronic conditions such as asthma, diabetes, HIV and AIDS, epilepsy, hypertension, mental health disorders and TB requires attention to:

- Adherence to long term pharmacotherapy-incomplete or non-adherence can lead to failure of an otherwise sound pharmacotherapeutic regimen.

- Organisation of health care services, which includes consideration of access to medicines and continuity of care

Patient Adherence

Adherence is the extent to which a person's behavior - taking medication, following a diet and/or executing lifestyle changes, corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health care provider.

Poor adherence results in less than optimal management and control of the illness and is often the primary reason for suboptimal clinical benefit. It can result in medical and psychosocial complications of disease, reduced quality of life of patients, and wasted health care resources.

Poor adherence can fall into one of the following patterns where the patient:

- takes the medication very rarely (once a week or once a month);

- alternates between long periods of taking and not taking their medication e.g. after a seizure or BP reading:

- skips entire days of medication;

- skips doses of the medication;

- skips one type of medication:

- takes the medication several hours late:

- does not stick to the eating or drinking requirements of the medication:

- adheres to a purposely modified regimen; and

- adheres to an unknowingly incorrect regimen.

Adherence should be assessed on a regular basis. Although there is no gold standard, the current consensus is that a multi method approach that includes self-report be adopted such as that below.

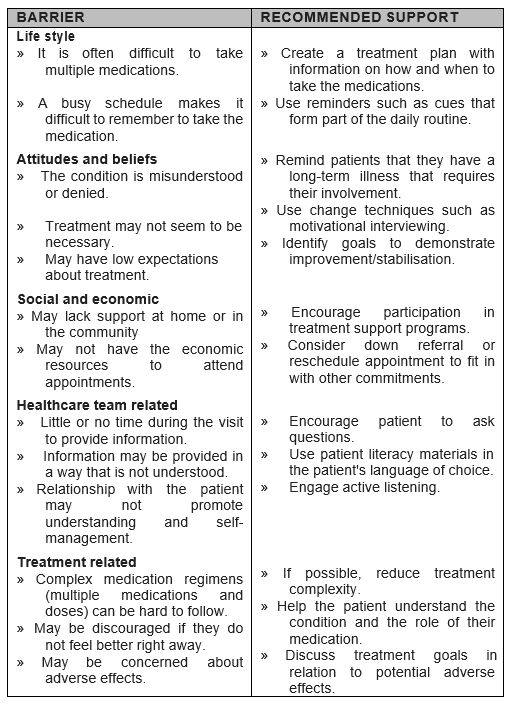

Barriers that contribute towards poor adherence

Although many of these recommendations require longer consultation time, this investment is rewarded many times over during the subsequent years of management.

For a patient to consistently adhere to long term pharmacotherapy requires integration of the regimen into his or her daily life style. The successful integration of the regimen is informed by the extent to which the regimen differs from his or her established daily routine. Where the pharmacological proprieties of the medication permits it, the pharmacotherapy dosing regimen should be adapted to the patient's daily routine. For example, a shift worker may need to take a sedating medicine in the morning when working night shifts, and at night, when working day shifts. If the intrusion into life style is too great, alternative agents should be considered if they are available. This would include situations such as a lunchtime dose in a school-going child who remains at school for extramural activity and is unlikely to adhere to a three times a day regimen but may very well succeed with a twice-daily regimen.

Towards concordance when prescribing

Establish the patient's:

- occupation,

- daily routine,

- recreational activities,

- past experiences with other medicines, and

- expectations of therapeutic outcome.

Balance these against the therapeutic alternatives identified based on clinical findings. Any clashes between the established routine and life style with the chosen therapy should be discussed with the patient in such a manner that the patient will be motivated to a change their lifestyle.

Note:

Education that focuses on these identified problems is more likely to be successful than a generic approach toward the condition/medicine.

Education points to consider

- Focus on the positive aspects of therapy whilst being encouraging regarding the impact of the negative aspects and offer support to deal with them if they occur.

- Provide realistic expectations regarding:

- normal progression of the Illness - especially important in those diseases where therapy merely controls the progression and those that are asymptomatic;

- the improvement that therapy and non-drug treatment can add to the quality of life.

- Establish therapeutic goals and discuss them openly with the patient.

- Any action to be taken with loss of control or when side effects develop.

- In conditions that are asymptomatic or where symptoms have been controlled, reassure the patient that this reflects therapeutic success, and not that the condition has resolved.

- Where a patient raises concern regarding anticipated side effects, attempt to place this in the correct context with respect to incidence, the risks vs. the benefits, and whether or not the side effects will disappear after continued use.

Note:

Some patient's lifestyles make certain adverse responses acceptable which others may find intolerable. Sedation is unlikely to be acceptable to a student but an older patient with insomnia may welcome this side effect. This is where concordance plays a vital role.

Notes on prescribing in chronic conditions.

- Do not change doses without good reason.

- Never blame anyone or anything for non-adherence before fully investigating the cause.

- If the clinical outcome is unsatisfactory- investigate adherence (remember side effects may be a problem here).

- Always think about side effects and screen for them from time to time.

- When prescribing a new medicine for an additional health related problem ask yourself whether this medicine is being used to manage a side effect.

- Adherence with a once daily dose is best. Twice daily regimens show agreeable adherence. However once the intervals increased to 3 times a day there is a sharp drop in adherence with poor adherence to 4 times a day regimens.

- Keep the total number of tablets to an absolute minimum as too many may lead to medication dosing errors and may influence adherence.

Improving Continuity of Therapy

- Make clear and concise records.

- Involvement the patient in the care plan.

- Every patient on chronic therapy should know:

- his/her diagnosis

- the name of every medicine

- the dose and interval of the regimen

- his/her BP or other readings

Note: The prescriber should reinforce this only once management of the condition has been established.

- When the patient seeks medical attention for any other complaints such as a cold or headache, he/she must inform that person about any other condition/disease and its management.

- If a patient indicates that he/she is unable to comply with a prescribed regimen, consider an alternative - not to treat might be one option, but be aware of the consequences e.g. ethical.